In Part 1 I discussed the increasing regulatory focus on cybersecurity, and what to expect in the short term. In this post I want to dissect the individual elements of cybersecurity, and list what you’ll need to do to demonstrate compliance on each one going forward. So here are the required elements of a cybersecurity program, followed by what you need to do:

- Governance – risk management and oversight

- Threat intelligence and collaboration – Internal & External Resources

- Third -party service provider and vendor risk management

- Incident response and resilience

1. Governance – risk management and oversight

Nothing new about this one, virtually all FFIEC IT Handbooks list proper governance as the first and most important item necessary for compliance, and governance begins at the top. In fact a recent FFIEC webinar was titled “Executive Leadership of Cybersecurity: What Today’s CEO Needs to Know About the Threats They Don’t See.” But governance involves more than just management oversight. The IT Handbook defines it this way:

“Governance is achieved through the management structure, assignment of responsibilities and authority, establishment of policies, standards and procedures, allocation of resources, monitoring, and accountability.”

What you need to do:

- Update & Test your Policies, Procedures and Practices. Verify that cyber threats are specifically included in your information security, incident response, and business continuity policies.

- Assess your Cybersecurity Risk (Risk = Threat times Vulnerability minus Controls). When selecting controls, remember that there are three categories; preventive, detective, and responsive/corrective. Preventive controls are always best, but given the increasing reliance on third-parties for data processing and storage, they may not be optimal. Focus instead on detective and responsive controls. Also, make sure your assessment accounts for any actual events affecting you or your vendors. Document both:

- Inherent cybersecurity risk exposure – risk level prior to application of mitigating controls

- Residual cybersecurity risk exposure – risk remaining after application of controls

- Adjust your Policies, Procedures and Practices as needed based on the risk assessment results.

- Use your IT Steering Committee (or equivalent) to manage the process.

- Provide periodic Board updates.

2. Threat intelligence and collaboration – Internal & External Resources

This element reflects both the complexity and the pervasiveness of the cybersecurity problem, and (unlike governance) is a particular challenge to smaller institutions (<1B). According to a study conducted in May of this year by the New York State Department of Financial Services, the information security frameworks of small institutions lagged behind larger institutions in two key areas: oversight over third party service providers (more on that later), and membership in an information-sharing organization.

What you need to do:

Regulators expect all financial institutions to identify and monitor cyber-threats to their organization, and to the financial sector as a whole. Make sure this “real-world” information is factored into your risk assessment. Some information sharing resources include:

- United States Computer Emergency Readiness Team (US-CERT) – www.us-cert.gov

- U.S. Secret Service Electronic Crimes Task Force (ECTF) – www.secretservice.gov/ectf.shtml

- FBI InfraGard – www.infragard.org

- Information Sharing and Analysis Centers (ISACs) – www.isaccouncil.org

- NCUA Cyber Security Resources – www.ncua.gov/Resources/Pages/cyber-security-resources.aspx

- FDIC Cyber Challenge: A Community Bank Cyber Exercise – www.fdic.gov/regulations/resources/director/technical/cyber/cyber.html

- Private sources of information, such as this blog, and this one.

3. Third -party service provider and vendor risk management

For the vast majority of outsourced financial institutions, managing cybersecurity comes down to managing the risk originating at third-party providers and other unaffiliated third-parties. As the Chairman of the FFIEC, Thomas J Curry, recently stated:

“One area of ongoing concern is the increasing reliance on third parties..The OCC has long considered bank oversight of third parties to be an important part of a bank’s overall risk management capability.”

Smaller institutions may be even more at risk, because they tend to rely more on third-parties, and (as I pointed out earlier) tend to lag behind larger institutions when it comes to vendor management. This is mostly because of available internal resources. Larger institutions may conduct their own compliance audits, while smaller institutions may rely more on external resources, such as SOC reports and FFIEC Reports of Examination (ROE). And once the reports are received, interpreting them to determine if they indeed address your concerns can be an even bigger challenge.

What you need to do:

Regardless of size, all institutions should employ basic vendor management best practices to understand and control third-party risk. Pay particular attention to the following:

- Pre-contract Planning & Due Diligence – in addition to reviewing the SOC reports and ROE’s, determine if the vendor had any significant recent security events.

- Contracts – they should define if and how you’ll be notified in the event of a security event involving you or your customer’s data, and who is responsible for customer notification. They should also include a “right-to-audit” clause, giving you the right to conduct audits at the service provider if necessary.

- Ongoing Monitoring – in addition to updated SOC reports, financials, and ROE’s, don’t forget to take advantage of vendor forums and user groups. As the FFIEC statement stressed:

“…financial institutions that utilize third party service providers should check with their provider about the existence of user groups that also could be valuable sources of information.”

- Termination/Disengagement – management should understand what happens to their data at the end of the relationship.

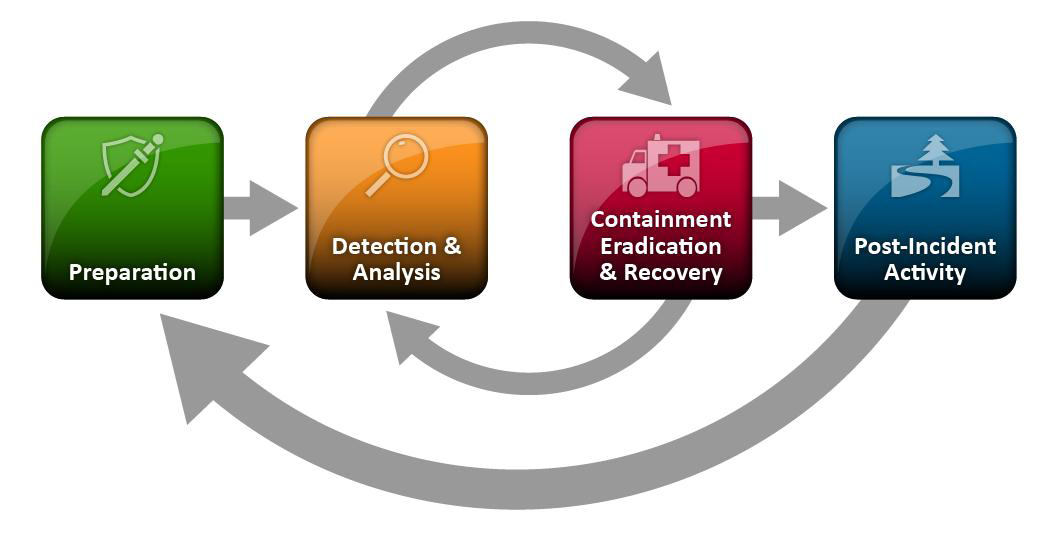

4. Incident response and resilience

Incident response has been mentioned in all regulatory statements about cybersecurity, and for good reason. Regardless of whether it originates internally or externally, a security incident is a virtual certainty. And regulators know that although vendor oversight does provide some measure of assurance, you have very little actual control over specific vendor-based preventive controls. So detective and corrective/responsive controls must compensate.

What you need to do:

Make sure your incident response program (IRP) has been updated to accommodate a response to a cybersecurity event. As I stated in Part 1, your existing policies should already do this if they are impact-based instead of threat-based. “Cyber” simply refers to the source or nature of the threat. The impact of a cybersecurity event is generally the same as any other adverse event; information is compromised or business is interrupted. However, all IRP’s should contain certain elements:

- The incident response team members

- A method for classifying the severity of the incident

- A response based on severity, to include internal escalation, and external notification.

- Periodic testing and Board reporting

Regarding testing, the FFIEC considers it so important they refer to it as one of the primary take-aways from their recent webinar, encouraging all institutions to consider:

How often is my institution testing its plans to respond to a cyber attack? Do these tests include our key internal and external stakeholders?

In summary, review the requirements for cybersecurity, and compare them with your current policies, procedures and practices. Hopefully you’ve already incorporated many (if not most) of these elements into your program, and very little adjustment needs to be made. But either way, be prepared to discuss what you are doing, and how you are doing it, with the regulators…they WILL be asking you.