Hey Guru!

Management is asking why we have to complete the FFIEC Cybersecurity Assessment Tool when it is voluntary. They feel it is too much work if it is not mandatory. I think it is still needed even though it is voluntary. Is there any documentation as to why it is still necessary for OCC banks to complete the Assessment?

The FFIEC issued a press release October 17, 2016, on the Cybersecurity Assessment Tool titled Frequently Asked Questions. This reiterated that the assessment is voluntary and an institution can choose to use either this assessment tool, or an alternate framework, to evaluate inherent cybersecurity risk and control maturity.

Since the tool was originally released in 2015, all the regulatory agencies have announced plans to incorporate the assessment into their examination procedures:

- OCC Bulletin 2015-31 states “The OCC will implement the Assessment as part of the bank examination process over time to benchmark and assess bank cybersecurity efforts. While use of the Assessment is optional for financial institutions, OCC examiners will use the Assessment to supplement exam work to gain a more complete understanding of an institution’s inherent risk, risk management practices, and controls related to cybersecurity.”

- Federal Reserve SR 15-9 states “Beginning in late 2015 or early 2016, the Federal Reserve plans to utilize the assessment tool as part of our examination process when evaluating financial institutions’ cybersecurity preparedness in information technology and safety and soundness examinations and inspections.”

- FDIC FIL-28-2015 states “FDIC examiners will discuss the Cybersecurity Assessment Tool with institution management during examinations to ensure awareness and assist with answers to any questions.”

- NCUA states “FFIEC’s cybersecurity assessment tool is provided to help them assess their level of preparedness, and NCUA examiners will use the tool as a guide for assessing cybersecurity risks in credit unions. Credit unions may choose whatever approach they feel appropriate to conduct their individual assessments, but the assessment tool would still be a useful guide.”

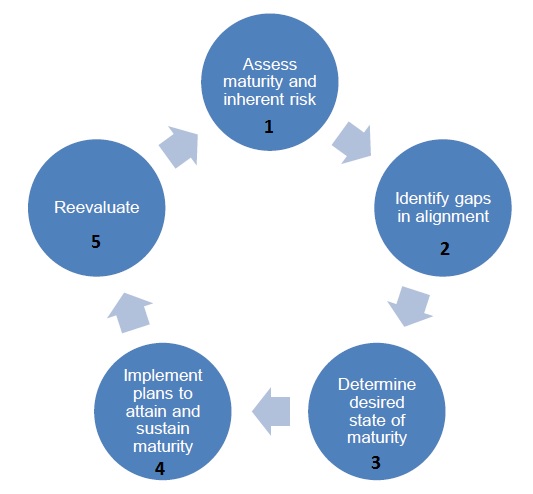

Even though the FFIEC format is officially voluntary, the institution still has to evaluate inherent risk and cybersecurity preparedness in some way. Therefore, unless you already have a robust assessment program in place, we strongly encourage all institutions to adopt the FFIEC Cybersecurity Assessment Tool format since this is what the examiners will use.

NOTE: The FAQ also made it clear that the FFIEC does not intend to offer an automated version of the tool. To address this, we have developed a full-featured cybersecurity service (RADAR) that includes an automated assessment, plus a gap analysis / action plan, cyber-incident response test, and several other components.